Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction is a book about how to become a superforecaster, an often ordinary person who has an extraordinary ability to make predictions about the future with a degree of accuracy significantly greater than the average.

In a landmark study undertaken between 1984 and 2004, Wharton Professor Philip Tetlock showed that the average expert’s ability to make accurate predictions about the future was only slightly better than a layperson using random guesswork. His latest project, which began in 2011, has since shown that there are some people with real, demonstrable predicting foresight. In his book, co-authored with Dan Gardner, Tetlock identifies how you can become a superforecaster too. Read on for a summery of how.

This article summarises the most interesting findings from the book. You can click the links below to jump to a section:

The one about the dart throwing chimpanzee

Superforecasting opens up with a spoiler; the punchline to a joke: the average expert is as accurate as a dart throwing chimpanzee.

It goes like this: A researcher gathered a big group of experts – academics, pundits, and the like – to make thousands of predictions about the economy, stocks, elections, wars, and other issues of the day. Time passed, and when the researcher checked the accuracy of the predictions, he found that the average expert did as well as random guessing. Except that’s not the punchline because ‘random guessing’ isn’t funny. The punchline is about dart throwing chimpanzees. Because chimpanzees are funny.

Philip Tetlock was the researcher that conducted that Expert Political Judgement study. He didn’t mind the joke because, he says it makes a valid point:

Open any newspaper, watch any TV news show, and you find experts who forecast what’s coming. Some are cautious. More are bold and confident. A handful claim to be visionaries able to see decades into the future. With few exceptions, they are not in front of the camera because they possess any proven skill at forecasting. Accuracy is seldom even mentioned… The one undeniable talent they have is their skill at telling a compelling story with conviction, and that is enough. Many have become wealthy peddling forecasting of untested value to corporate executives, government officials and ordinary people who would never think of swallowing medicine of unknown efficacy and safety but who routinely pay for forecasts that are as dubious as elixirs sold from the back of a wagon.

But Tetlock realised that his message was mutating. Whilst his research showed that the average expert had done little better at predicting specific futures, there were actually two statistically distinguishable groups of experts: the first failed to do better than the chimp (and often worse) but the second beat the chimp (though not by a wide margin).

So why did one group do better than the other? It wasn’t whether they had PhDs or access to classified information. Nor was it what they thought – whether they were liberal or conservative, optimists or pessimists. The critical factor was how they thought.

This led Tetlock to develop his second major piece of research: the Good Judgement Project, which commenced in 2011 in association with IARPA (part of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence in the US), who were interested to know whether ordinary people, without access to highly classified intelligence information, could make better forecasts about geopolitical events than professional analysts supported by a multi-billion dollar apparatus. It turned out that they could: the top forecasters in the Good Judgement Project were 30% better than intelligence officers with access to actual classified information, and 60% better than the average.

Are you a fox or a hedgehog?

Those who displayed poorer superforecasting skills tended to organise their thinking around Big Ideas. They sought to squeeze complex problems into the preferred cause-effect templates. They were usually confident and likely to declare things ‘impossible’ or ‘certain’. Committed to their conclusions, they were reluctant to change their minds even when their predictions had clearly failed.

The other group consisted of more pragmatic experts. They gathered as much information from as many sources as they could. They talked about possibilities and probabilities, not certainties. They readily admitted when they were wrong and changed their minds.

The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

The Hedgehog & The Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy’s View of History by Isiah Berlin

Inspired by Isiah Berlin’s thinking, Tetlock dubbed the Big Idea experts ‘hedgehogs’ and the more eclectic experts ‘foxes’. Foxes beat hedgehogs, and not just by playing it safe with mediocre probabilities, but with calibration and resolution. Foxes had real foresight, hedgehogs didn’t. In fact, in the EPJ research, when hedgehogs made forecasts on the subject they knew the most about – their own specialities – their accuracy declined.

Summary of Superforecasting skills

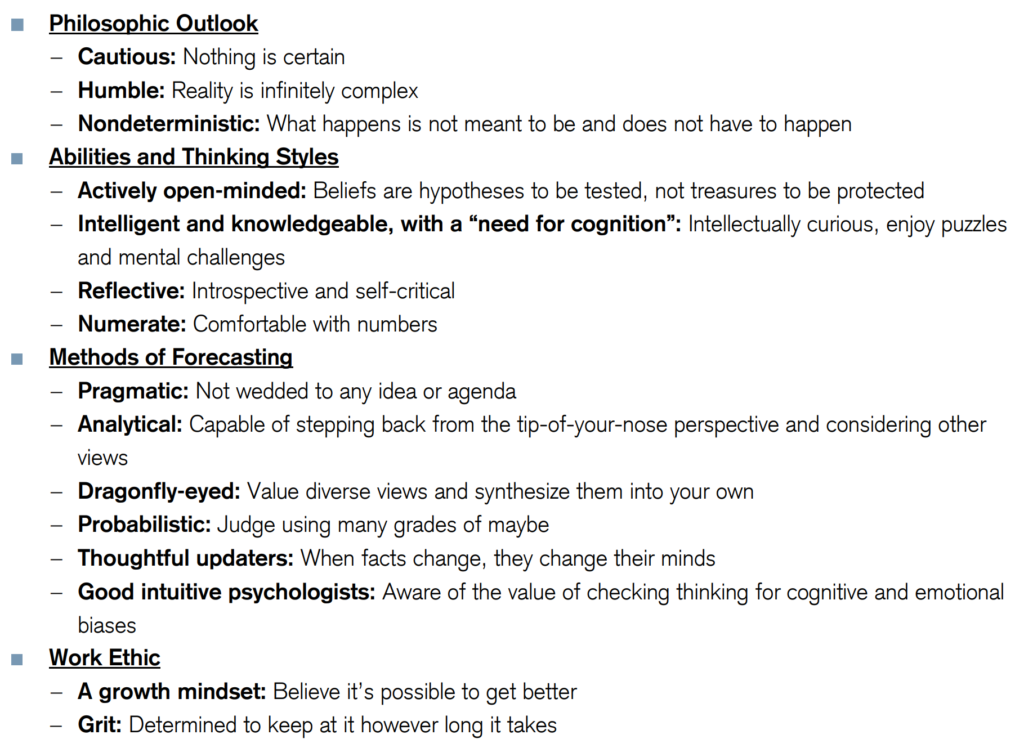

Check out this superb summary for Sharpening Your Forecasting Skills:

The most important superforecasting skill? Perpetual beta

Evolution has seen to it that humans are hardwired to hate uncertainty. The antidote to uncertainty is prediction.

Our ancestors ability to predict the whereabouts of the local tiger (so as to avoid it) or a wooly mammoth (so as to to be able to hunt, kill and eat it) significantly increased their chances of survival. In modern times, we like to be able to predict where the next pay cheque is coming from, or whether or not one country might start a war with another, because that too affects our survival. Whatever the situation, the bio-chemical reaction in our brains have not changed for millions of years: sending messages from our neo-cortex, uncertainty about the future generates a strong threat or alert response in our brain’s limbic system, leaving us with a distinct feeling of unease.

In an effort to counter uncertainty, we try to predict the future. Whilst humans may not, in general, be very good at that task, Superforecasting does at least do an excellent job in helping us to improve. And whilst there are a variety of skillsets that will help, Tetlock and Gardner identify one factor that will most likely help you to become a superforecaster:

The strongest predictor of rising into the ranks of superforecasters is perpetual beta – the degree to which one is committed to belief updating and self-improvement. It is roughly three times as powerful a predictor as its closest rival, intelligence.

I’m Richard Hughes-Jones, an Executive Coach to CEOs and senior technology leaders.

My clients are transitional founders, CEOs and executives in high-growth technology businesses, the investment industry and progressive corporates.

Having often already mastered the technical aspects of their craft, I help my clients navigate the complex adaptive challenges associated with executive-level leadership and growth.

Find out more about my Executive Coaching services and get in touch if you’d like to explore working together. You can also read my Complete Guide to Finding the Right Executive Coach for You.