Perhaps the self-improvement literature’s biggest act of mis-selling is telling us that if we want to improve at anything then we need to undertake deliberate practice. According to one guru “regardless of where we choose to apply ourselves, deliberate practice can help us maximize our potential”. It sounds enticing, but it’s incorrect. Deliberate practice won’t necessarily help you achieve mastery regardless of where you choose to apply yourself.

Table of Contents

This article is part of my Accelerating Executive Mastery >> series.

In business, leadership and life, discover the common factors intrinsic to developing mastery in a complex world.

What is Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice is a focused and systematic approach to improving skills and achieving expertise.

It involves repetitive practice of challenging tasks, continuous feedback, and a structured effort to go beyond current abilities. Unlike regular practice, which often involves repeating known tasks, deliberate practice is about pushing the boundaries of one’s capabilities and addressing weaknesses. It requires significant time, usually around a decade or more, and often includes the guidance of skilled coaches. Key elements include setting specific goals, maintaining high levels of concentration, and undergoing rigorous self-assessment.

K. Anders Ericsson on deliberate practice

Swedish psychologist and academic K. Anders Ericsson was one of the earliest researchers to explore the psychological nature of expertise and human performance. Ericsson studied expert performance in domains like medicine, music, chess, and sports, focusing exclusively on what he called ‘deliberate practice’ as a means of understanding how expert performers acquire superior performance. Here’s what he had to say about it:

The journey to truly superior performance is neither for the faint of heart nor for the impatient. The development of genuine expertise requires struggle, sacrifice, and honest, often painful self-assessment. There are no shortcuts. It will take you at least a decade to achieve expertise, and you will need to invest that time wisely, by engaging in “deliberate” practice – practice that focuses on tasks beyond your current level of competence and comfort. You will need a well-informed coach not only to guide you through deliberate practice but also to help you learn how to coach yourself. Above all, if you want to achieve top performance as a manager and a leader, you’ve got to forget the folklore about genius that makes many people think they cannot take a scientific approach to developing expertise.

The Making of an Expert, by K. Anders Ericsson, Michael J. Prietula, and Edward T. Cokely (2007)

The problem with Deliberate Practice, for improving at anything

To be fair to the gurus, Ericsson himself says in the introduction to his book Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise that the principles of deliberate practice “can be used by anyone who wants to improve at anything, even just a little bit”. Perhaps that’s true for individuals early on in their learning journeys. But the type of structured development that it supports won’t help those at a more advanced stage in their career. Something Ericsson himself knew to be true:

Deliberate practice is defined as possible only in domains with a long history of well-established pedagogy [the study and practice of teaching]. In other words, deliberate practice can only exist in fields like music and math and chess. K. Anders Ericsson lays out this narrow definition in Peak, and then does a cop-out, arguing that while he hasn’t studied practice outside of such domains, the ideas from deliberate practice may be applied to pedagogically less established fields.

Why Tacit Knowledge is More Important Than Deliberate Practice, by Cedric Chin

Cedric takes his criticism of deliberate practice down the Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) path, which he argues is a much more useful way of improving performance in complex domains that have less clear methods of teaching and practice. NDM explains how experts like fighter pilots, fire fighters, doctors etc use tacit knowledge and intuition to get to better solutions, quicker. But the problems in hand are often technical, operational, and proximally complex i.e. outcomes will be known and can be evaluated within a relatively short space of time (mintes and hours).

But some professions deal with more distally complex challenges i.e. outcomes will only be known over much longer time horizons (months and even years). Aspects of business and leadership are great examples. So too, investing and economics. Basically, any sociotechnical system that involves making judgements in relation to things about which the outcome won’t be known until well into the future.

Professionals in these disciplines have to work at a much higher level of abstraction. They must work with information and feedback that is messy, random, incomplete, unrepresentative, ambiguous, inconsistent, unpalatable, or secondhand. Where the relationship between cause and effect isn’t known until afterwards. Where what worked once may not work again. Where the challenges are so complex that there isn’t any single answer. Where it’s not possible to just ‘know better’ based on previous experience. Where there’s tensions, tradeoffs and paradox. And where it’s neccessary to look not just inwards to their own expertise but also outwards, to soak up the perspectives and collective wisdom of organisations, competitors and markets.

In these sorts of situations, NDM is less helpful. If you’re at the stage in your career where you’re responsible for making these types of judgements and decisions, then deliberate practice isn’t going to help you much.

The Future Of Leadership

A monthly newsletter packed full of leadership wisdom for founders, CEOs & senior technology executives.

Where Deliberate Practice works well, and not so well

Beyond the pedagogical case for deliberate practice – that it only works well in fields with well-established teaching methods that provide clear guidance on what to practice and how to practice it – there are various other ways to frame its usefulness. Robin Hogarth’s work on kind and wicked learning environments is one of the most helpful.

Kind Learning Environments

Kind learning environments include most sports, disciplines like chess, and subjects like learning languages or maths. It’s not that some of these pursuits aren’t tough and require outstanding levels of grit, determination and resilience to perform at the highest levels, but the rules of the game are fixed, the outcomes of actions are evident and feedback is fast and clear.

If you ever played tennis, or whenever you watch professional players, you realize that one has to make many decisions on the court. It’s a complex and uncertain game. Hard to learn and perfect. But it has one crucial advantage. In tennis, like in most other sports, we typically learn the right lessons from experience.

Unless we close our eyes and ears, we can clearly see what actions have which consequences. There are hundreds of interactions, which provide immediate, accurate, and abundant feedback to everyone involved. Professional players also have coaches, who know their stuff and provide objective assessments. And the rules of the game don’t suddenly change. Gravity, for example, doesn’t stop operating in the middle of a match.

Experience: Kind vs. Wicked, Learning the right lessons to improve decisions

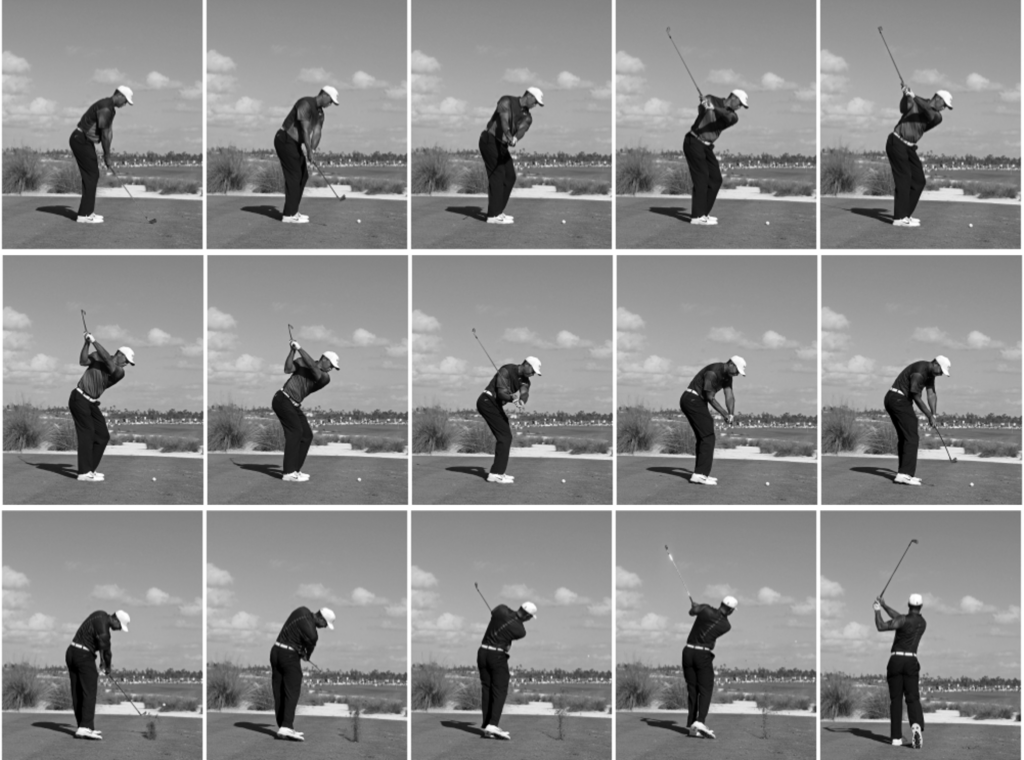

Kind learning environments lend themselves to established pedagogy which, when combined with the kind of repetitive, structured actions that go in to deliberate practice, means it works very well. This is why the self-help literature will tell you that deliberate practice is central to mastery, citing examples of how Tiger Woods or Josh Waitzkin applied it to become world champions. In the next paragraph, they’ll roll the principles of deliberate practice over into business and explain how you can follow them to become the next Steve Jobs. But this is massively over-simplified.

Wicked Learning Environments

That’s because much of business, leadership and life doesn’t take place in the types of kind learning environments described above. It takes place in wicked learning environments, that don’t lend themselves well to rote teaching and practice. In the real world the rules of the game aren’t fixed and might not be decided by you. Learning is more challenging due to the dynamic, complex nature of the environment, contextual influences. Feedback is delayed, inaccurate, or misleading, often leading to persistent errors and misconceptions and making it hard to learn from actions.

The world does not play fair. Instead of providing us with clear information that would enable us to ‘know’ better, it presents us with messy data that are random, incomplete, unrepresentative, ambiguous, inconsistent, unpalatable, or secondhand.

How We Know What Isn’t So, by Thomas Gilovich

Business strategy, business models and capital allocation, anything involving interpersonal dynamics (e.g. organizational design and culture), externalities (e.g. competitors), trading and investing, economics and Central Banking all constitute wicked learning environments.

Feedback, Deliberate Practice & Mastery

The defining difference between what constitutes a kind and wicked environment, and the impact that this has on deliberate practice and mastery is feedback. Or, more specifically, the rate and quality of feedback.

In kind environments, like learning to play tennis or chess, feedback is immediate and accurate, allowing us to quickly adjust our actions and improve.

In wicked environments feedback can be long-delayed or erroneous, leading to poor decisions and misjudged confidence. It might take 6 months to know whether creating that new Chief Product Officer position was a good idea. Did that organisational restructure directly improve operating efficiency? Will that Series A investment return the fund? Venture capitalist investors must wait at least 5 years to find out. Will buying NVIDIA stock today ($124) turn out to be a good long term investment, or not? Were those three consecutive 25 basis point rate cuts by the Federal Reserves enough to tame inflation?

Feedback enables us to correct misunderstandings and learn from our mistakes, highlight blind spots and areas where we may lack awareness or insight, open ourselves up to diverse perspectives and ultimately adapt and update our mental models accordingly. Without it, we’re operating in a very different context and context changes everything.

None of which is to say that deliberate practice is uneccessary to gain expertise and mastery. It’s vital for developing skills in the types of kind environments described above. Even in wicked environemnts, engaging in deliberate practice earlier on in our careers help us develop our explicit knowledge and build the foundational base upon which we can construct increasingly advanced, abstract mental models of how the world works. But for navigating the types of increasingly abstract, wicked problems and environments that challenge us later on in our careers, it’s of less value.

My next article goes even deeper into the limitations of deliberate practice for executive-level leadership.

I’m Richard Hughes-Jones.

I’m an Executive Coach to founders, CEOs and senior technology leaders in high-growth technology businesses, the investment industry and progressive corporates.

Having often already mastered the technical aspects of their craft, I help my clients navigate the complex adaptive challenges associated with executive-level leadership and growth.

I’m based in London and coach internationally. Find out more about my Executive Coaching services and get in touch if you’d like to explore working together.